列举web应用程序设计中常见的10种错误

作者:Jakob Nielsen

撰写有关应用程序设计错误的文章是件很困难的事情,因为最糟糕的错误往往具有领域专门性和特殊性。通常情况下,应用程序的失败有以下3种原因:解决了错误的问题;目标问题正确,但使用的是错误的功能;功能设计正确,但过于复杂使得用户难以理解。

这3个错误都可能导致应用的失败,而我却还无法告诉你怎么做才是正确的。什么才是正确的问题?什么是正确的功能?何种程度的功能复杂性才恰当?对于各个领域和用户类别来说,这些问题的答案都有所不同。

以下是唯一能够提供的通用建议:你应当以用户研究为基础来做出决定,而不是依靠自己的主观猜测和臆想。

1、在决定应用的功能前,先开展领域研究和任务分析。

2、在进行更为细节化的设计前,先在纸上构建初始想法的原型。这可以避免资源的浪费,因为你在获得用户反馈后还可能修改想法。

3、不断改良设计,通过多轮的快速用户测试来润色应用功能。

当然,开发者们都知道他们需要测试应用UI,需要将半成品提供给真正的用户来查看应用程序的运转情况。

通常的想法是,程序员应当待在房间里竭尽全力地编程。我的观点刚好相反:参与应用开发和制作的所有人都应当花点时间来观察最终用户的行为。

无论你喜欢怎么做,至少要保证做到这点:不要只根据“用户代表”或“商业分析师”的意见来设计应用功能。让应用可用性产生偏差的最普遍错误做法是,只倾听用户的说法而没有亲眼看到他们的做法。用户需求说明并不总是对的。你必须快速地根据需求构建出原型,向用户展现某些具体的东西,由此来探究他们真正需要的东西。

以下是我总结的10种常见的可用性设计错误:

1、非标准GUI控制

基础GUI部件组成对话设计词典的词汇单位,包括指令链接和按钮、单选按钮和检验栏、滚动条和检验栏。如果你改变了这些单位的外观或行为,就好比忽然在母语交谈中插入外语词汇,这会让交流者感到困惑。

出于某些原因,设计中最普遍出现问题的是滚动条。多年以来,我们在研究中遇到过许多非标准滚动条,它们往往会让用户忽视某些选项。

30年来,世界上最棒的互动设计师已经润色了GUI控制的标准外观和功能,完美地通过了数千个小时的用户测试。所以说,你在周末两天时间就能够发明出更好的按钮,这几乎是不可能的。

但是,假设你自行设计的控制比标准控制更加优越,但依然会与整个世界显得格格不入。毕竟用户已习惯于多年所使用的标准GUI,他们使用你的对话框控制方式时仍会感到不适——用户对标准GUI控制方式的使用经验要比对新设计的使用多数千倍。

如果UI运行控制方式这样基本的内容同用户预期有所偏差,那么用户很可能无法适应这种新应用。即便他们能够成功使用,那么也需要耗费大量的脑力来执行本该极为简单的操作。最好让用户的认知资源放在理解应用功能如何帮助他们实现目标上。

1.1、伪GUI控制方式

相反,在某些设计中,有些设计并非GUI控制方式,但是却模仿GUI来设计,这对可用性的影响更加严重。我们经常会看到看似链接的文字和标题(游戏邦注:比如使用不同颜色或下划线),但是却无法点击。当用户点击这些内容后发现什么也没发生,他们会认为这个站点存在错误。所以,请遵守视觉化链接的设计指导。

同样的问题还包括,看似按钮的东西无法产生动作,或看似单选按钮却无法进行选择。在本轮研究中,我们发现了一个这样的例子。

要在Liste Rouge Paris上设计自行裁剪的衬衫,你必须提供尺寸。正如以下截屏所显示的那样,这里的应用已经设计了两种不同的路径,客户可以根据裁缝是否已记录自身尺寸来做出选择。

我们的测试用户会不停点击“新顾客”按钮,由此来表明他确实是个新顾客。不幸的是,该屏幕元素并不是个按钮,只是个无法点击的标题而已。

他是唯一测试这个站点的用户,因为他是在用户自行选择访问站点(游戏邦注:通常来自于搜索引擎列表)的任务中碰巧遇到这个站点的。在这种情况下,该用户最终解除了困惑,继续输入自己的尺寸。如果我们测试更多的用户,很可能有小比例用户会在这种情况下放弃。对话设计中的每个小错误只会对其使用造成些许影响,但是多数UI中包含大量的错误,流失的顾客数量也就会逐渐攀升。

除此之外,这个屏幕还错误地使用了单选按钮。从理论上来说,这5个选择是不能共存的,所以才会用上单选按钮。但是在用户理解工作流程的心智模型中,这个界面却要同时解决两个问题:1)新顾客和老顾客;2)如何提供尺寸。应当只针对用户要解决的当前问题提供一套单选按钮。

所以,在上文所示范例中,较好的设计应该是,首先让用户选择是新顾客还是老顾客,然后根据他们的选项提供相应的单选按钮。

2、不一致性

非标准化GUI控制是不一致性设计普遍问题的特殊案例。

当应用程序在相同的功能中使用不同的词汇或命令,或者当应用程序中相同词汇在不同部分代表不同概念时,困惑就会产生。同样,当事物违反呈现惯例时,用户也会感到困惑。

在同一个应用中,使用相同的名称来指代相同的功能,会让应用的使用变得更为简单。

谨记以下规则:差异就等同于困难。

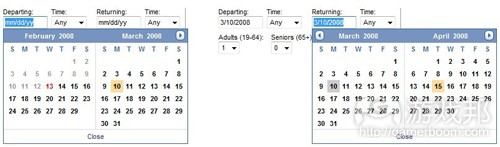

以下是我们当前研究中发现的例子:Expedia在用户指定旅程的出发或返回日期时会跳出两个月的历表。以下截屏显示的是在2月份时计划3月10日出发和3月15日返回的旅程的呈现情况。

在第2个弹出窗口中,3月移到了左边,右边显示的是4月。这似乎看起来是个高明的举动,因为旅程出发日期是3月,所以返回时间不可能是2月。

但事实上,用户会习惯于在右边的日历中寻找3月15日。

在我们的测试中,第2个弹出窗口中的月份位置变化会使用户感到困惑和延迟,但用户最终都能够明白过来。我们只用这个站点测试了为数不多的用户,但是如果你观察用户测试中这种几乎被忽视的错误,就会发现确实有可能在使用中犯错。

返回日期设定的错误可能导致严重的后果,顾客到达机场后却发现自己没有乘坐计划航班的机票。如果该站点有良好的确认邮件系统,用户可能会在出门前发现问题,但是这依然会使顾客感到愤怒,导致其不得不费力解决这种尴尬处境。

即便用户最终能够正确地使用日历,因不一致性设计而浪费的时间也要多于点击下个月按钮所需的时间。

这种设计只能够节省那些已经熟练操作此类UI的用户时间。所以,专业旅行社的应用程序或许可以使用类似Expedia的日历设计。针对普通消费者的站点则不提倡采用这种方法。

3、缺乏预知可用功能

“可用功能”指你能够使用对象来做的事情。比如,检验栏可用来打开和关闭页面,滚动条可用来上下移动页面。“预知可用功能”指你在使用前只需看到对象就理解的动作。

预知可用功能在UI设计中特别重要,因为所有的屏幕像素都可以点击,即便有些区域在点击后毫无变化。电脑屏幕上有这么多的可见内容,用户不可能有足够的时间一一尝试来寻找可以产生动作的选项。有时候小孩子喜欢点击屏幕上的内容来探索各种功能,这属于例外情况。

就拖动和放置设计而言,如果能够被拖动的事物或能够被放置的地方设计得不明显,那往往会成为最易冒犯用户的设计。相比之下,简单的检查栏和命令按钮已经足以显示用户可点击的内容。

常见的预知可用功能缺乏现象如下所示:

(1)用户说:“我能在这里做什么?”

(2)用户完全没有发现对他们有所帮助的功能。

(3)试图使用丰富的屏幕文字来解决这两个问题(游戏邦注:更糟糕的是,在你完成前面数个操作时,原先冗长而多级的操作指示就消失了)。

我在20世纪80年代测试首批Macintosh应用程序时,用户往往会对打开MacWrite等应用后呈现出的空白屏幕感到手足无措。我要用这个应用程序来做什么呢。首个步骤应当是创建新文件,但是这个命令并没有呈现在屏幕上,除非你碰巧下拉了“文件”菜单。随后,该应用程序发布更新,在打开程序所呈现的屏幕上添加打开空白文件的选项,用闪烁的光标来呈现“开始输入”的预知可用功能。

3.a、点击目标很小

这里还有个问题,就是点击目标过小,导致用户无法精确点击到合适的区域。即便用户正确地察觉到了相关可用功能,他们常常也会改变想法,开始认为这些功能是不存在的,因为他们点击后什么事情也没发生。对老年用户或有肢体技能障碍的用户来说,点击区域过小的问题特别严重。

4、缺乏反馈

就对话框可用性的提升而言,最基本的指导意见之一就是提供反馈:

(1)向用户展示系统的当前状态。

(2)告诉用户他们的命令已经被执行。

(3)告诉用户正在发生的事情。

如果站点保持沉默,用户便会开始猜测,而他们的猜测往往都是错误的。

有关反馈情况不良的实例,可以参考VW的汽车配置页面。因为用户无法分辨自己选择的是何种轮胎,所以在设计自己偏好的汽车时会遇到问题。

4.a、运转时未显示进程指示器

缺乏反馈的变体之一是,系统未向用户告知需要花较长时间才能完成动作。用户常常会认为应用程序已崩溃,或者会开始点击新的动作。

如果你无法在短时间内完成动作,要将这种情况告知用户,让用户知道正在发生的事情:

(1)如果命令的执行需要1秒以上的时间,显示“繁忙”指针。这就相当于告诉用户先暂停发出命令,不要点击其他的功能,直到指针变回原样。

(2)如果命令的执行需要10秒以上的时间,要呈现显眼的进度条,最好能够在指示器中显示完成百分比,除非你无法计算出运行中需要完成的剩余工作量。

5、不良错误消息

错误消息是种特别形式的反馈,它们告知用户错误已发生。错误消息设计指导原则已面世了将近30年,但许多应用程序仍然没有遵从。

最普遍的错误是,错误消息只向用户告知已发生的错误,没有解释原因,也没有建议用户要如何解决问题。此类消息会将用户置于困境中。

信息型错误消息不仅能够帮助用户解决当前问题,还能够为用户提供指导。通常情况下,用户不会花时间阅读手册和学习功能,但如果你清晰解释的话,他们会花时间来理解错误情况,因为他们想要解决问题。

web上的错误消息还有种较为普遍出现的问题:用户会忽视多数web页面上的错误消息,因为他们要处理的信息相当多。显然,简化页面是缓和这个问题的方法之一,但让错误消息更突出地显示在基于web的UI上也是必要措施。

6、重复询问相同的信息

不应当让用户多次输入相同的信息。毕竟,电脑很擅长进行数据记忆。用户需要重复输入信息的唯一原因在于,程序员偷懒,未将答案设置从应用的一部分传输到另一部分。

7、没有默认值

设置默认值能够给用户带来诸多便利,比如:

(1)缩短互动时间,如果用户能够接受默认值的话,就无需再输入新数值

(2)指导用户要以何种类型的答案来回答问题

(3)直接引导用户获得普遍结果,如果用户不知道要怎么操作的话,他们只需接受默认值即可

我在第1个错误中将Liste Rouge Paris作为反例,我打算在这里呈现它优秀的一面。对于自行设计预定衬衫的用户,裁缝提供了15种不同的衣领风格。幸运的是,他们还提供了默认选择。在测试中,这种做法对首次使用该应用的用户非常有效,因为当用户没有特别偏好时,保持默认选择便可以让他获得最普通和适合的衣物。

8、过早向用户呈现核心内容

多数基于web的应用都是短暂应用,是用户在浏览网页时碰巧遇到的。即便用户是在有意寻找新应用,他们往往也是在缺乏运转概念模型的情况下接触应用。人们不知道其工作流程或步骤,他们不知道预期结果,不了解他们将操纵应用的基本概念。

对于传统应用程序而言,这不是个大问题。即便用户从未使用过PowerPoint,他们可能也曾经观看过别人展示幻灯片。因而,新的PowerPoint用户在首次双击图标打开应用之前,便对该应用程序有了大概的了解。

对于关键任务应用程序的设计而言,你往往可以假设多数用户之前已经多次试用过应用。你还可以假设,新用户在亲眼看到UI之前,会接受一定时间的培训。至少,他们附近应该会有能够给予建议和指点的同事。而且,优秀的老板会告诉新员工有关应用程序的背景信息,比如为何要使用该应用程序以及需要借此完成的任务。

不幸的是,以上这两种情况都不适用于多数基于web的应用程序。它们甚至都无法适用于许多局域网应用程序。

如果过早地直接向用户呈现应用程序的核心组件,便会对可用性产生影响。不幸的是,多数用户不会去阅读使用说明,所以你或许需要向他们展示简单的列表或者通过单幅图片让他们一眼便可以抓住应用程序的要点。

比如,如果Hamilton Shirts“制作自己的衬衫”流程的首个屏幕就呈现设计完成的衬衫并带有“添加到购物车”按钮,那么想要订购自选尺寸衬衫的测试用户就会感到极为困惑。这个屏幕中有两个暗示内容:配置器和电子商务产品屏幕。

在这种情况就不应当使用默认值:想要自行设计衬衫的用户不可能会去购买呈现在首个屏幕上的已设计衬衫。

这个屏幕还犯了第1个错误,使用非标准GUI控制。标签化对话框中的非标准下拉选择菜单看上去并不像是标签,额外增加的布料展示也使得屏幕看上去像是非标准化的页面。如此呈现控制方式,用户很可能不知道如何选择布料。

在这个站点上,我们的测试用户无法理解要如何自行设计衬衫,最终选择了其他的站点。

9、不告知信息的使用方式

这个问题的严重性足以让我们将其单独列举出来:让用户输入信息却不告诉他们你将如何使用。

经典案例便是某公告板应用程序在用户的注册过程中要求其输入“昵称”。许多用户并没有意识到昵称将被用来识别他们所发布公告的剩余时间,所以他们通常输入的都是些不恰当的内容。

我们曾经测试过某个电子商务网站,该站点在用户看到产品页面前便要求他们输入邮编。这会让用户产生巨大的反感,许多用户出于隐私方面的顾虑而离开站点。人们讨厌那些探听隐私的站点。换种设计方法可能效果会更好:向用户解释站点需要知晓用户的住址,这样才能够根据购买产品的重量来计算邮费。

10、系统中心功能

许多应用程序提供的是反映系统内部数据而不是玩家能够理解的问题功能。

在我们的当前研究中,有个用户想要重新分配自己的退休储蓄(游戏邦注:比如增加债券的投资,减少股票投资)。她觉得自己达到了目标,但事实上她改变的只是将来进入退休账户的金钱投资分配。她的现有投资依然没有发生改变。

共同基金公司需将新投资和当前投资区分开来。重新分配未来增加的款项意味着修改新进入账户的金钱投资。重新分配当前投资意味着出售某些现有共同基金中的持有股份,使用重新分配选项购买相应投资。

我们的测试用户并没有意识到新旧资金间的区别,她只是想要根据修改过的投资策略重新分配退休储蓄。

即便用户理解了新旧资金间的区别,他们或许也希望能够将退休储蓄视为整体来对待,无需对新旧资金分别做决定。

较好的做法是,应用程序将修改整个账户的分配作为主功能,用高级设置来服务那些想要区别对待新旧资金的人。

附:web表格上的重置按钮

这个错误与web表格有关,但是许多应用程序都会用到大量的表格,所以我将该错误放在这个列表中。在web表格上设置重置按钮是种错误的做法。

重置按钮会清除用户所有已输入的信息,使表格回到初始状态。如果用户需要不断在相同的表格中填写完全不同的数据,或许会需要这个功能,但这种情况几乎从未在网页上发生。

用户很容易因一次错误的点击而失去所有的数据,这违反了最基本的可用性原则。我们应当尊重和保护用户的工作成果,所以需要为最具潜在破坏性的动作添加确认对话框。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2008年2月19日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Top-10 Application-Design Mistakes

Jakob Nielsen

It’s hard to write a general article about application design mistakes because the very worst mistakes are domain-specific and idiosyncratic. Usually, applications fail because they (a) solve the wrong problem, (b) have the wrong features for the right problem, or (c) make the right features too complicated for users to understand.

Any of these three mistakes will doom your app, and yet I still can’t tell you what to do. What’s the right problem? What are the right features? What complicating curlicues can safely be cut from those features? For each domain and user category, these questions have specific and very different answers.

The only generalizable advice is this: rather than rely on your own best guesses, base your decisions on user research:

Conduct field studies and task analysis before deciding what your app should do.

Paper prototype your initial ideas before doing any detailed design – and definitely before wasting resources implementing something you’d have to change as soon as you get user feedback.

Design iteratively, conducting many rounds of quick user testing as you refine your features.

Of course, people don’t want to hear me say that they need to test their UI. And they definitely don’t want to hear that they have to actually move their precious butts to a customer location to watch real people do the work the application is supposed to support.

The general idea seems to be that real programmers can’t be let out of their cages. My view is just the opposite: no one should be allowed to work on an application unless they’ve spent a day observing a few end users.

(Whatever you do, at least promise me this: Don’t just implement feature requests from “user representatives” or “business analysts.” The most common way to get usability wrong is to listen to what users say rather than actually watching what they do. Requirement specifications are always wrong. You must prototype the requirements quickly and show users something concrete to find out what they really need.)

All that said, there are still plenty of general guidelines for application UIs – so many, in fact, that we have a hard time cramming the most important into our two-day course. Here’s my list of 10 usability violations that are both particularly egregious and often seen in a wide variety of applications.

1. Non-Standard GUI Controls

Basic GUI widgets – command links and buttons, radio buttons and checkboxes, scrollbars, close boxes, and so on – are the lexical units that form dialog design’s vocabulary. If you change the appearance or behavior of these units, it’s like suddenly injecting foreign words into a natural-language communication. Det vil gøre læserne forvirrede (or, to revert to English:

Doing so will confuse readers).

For some reason, homemade design’s most common victims are scrollbars. For years, we’ve encountered non-standard scrollbars in our studies, and they almost always cause users to overlook some of their options. We’re seeing this again this year, in the studies we’re conducting to update our course on Fundamental Guidelines for Web Usability.

Some of the world’s best interaction designers have refined the standard look-and-feel of GUI controls over 30 years, supported by thousands of user-testing hours. It’s unlikely that you’ll invent a better button over the weekend.

But even if your homemade design, seen in isolation, were hypothetically better than the standard, it’s never seen in isolation in the real world. Your dialog controls will be used by people with years of experience operating standard GUIs.

If Jakob’s Law is “users spend most of their time on other websites,” then Jakob’s Second Law is even more critical: “Users have several thousand times more experience with standard GUI controls than with any individual new design.”

Users will most likely fail if you deviate from expectations on something as basic as the controls to operate a UI. And, even if they don’t fail, they’ll expend substantial brainpower trying to operate something that shouldn’t require a second thought. Users’ cognitive resources are better spent understanding how your application’s features can help them achieve their goals.

1.a. Looking Like a GUI Control Without Being One

The opposite problem – having something that looks like a GUI control when it isn’t one – can reduce usability even more. We often see text and headlines that look like links (by being colored or underlined, for example) but aren’t clickable. When users click these look-alikes and nothing happens, they think the site is broken. (So please comply with guidelines for visualizing links.)

A similar problem occurs when something looks like a button but doesn’t initiate an action, or looks like a radio button but isn’t a choice. We found an example of this in our current round of studies.

To design a custom-tailored shirt on Liste Rouge Paris, you must provide your measurements. As the following screenshot shows, there are two different paths through the application here, depending on whether your measurements are already on file with the tailor.

Our test user clicked incessantly on the New Customer button to indicate that he was indeed a new customer. Unfortunately, this screen element was not a button at all, but rather a non-clickable heading.

He was the only user to test this site because he encountered it during a task in which users could choose a site to visit (usually from a search listing). In this case, the user eventually overcame the confusion and proceeded to enter his measurements. If we had tested more users, a small percentage would have likely failed at this point. Each small error in dialog design reduces usage only by a small amount, but most UIs contain bundles of errors, and the number of lost customers adds up.

As an aside, this screen also uses radio buttons incorrectly. In theory, all five choices are mutually exclusive, which does call for radio buttons. But in the user’s mental model of the workflow, there are actually two issues here: (a) new vs. old customers, and (b) how to provide the measurements for your situation. You should use a single set of radio buttons only when users will choose between options for a single issue.

So, in the case above, a better design would first ask users to decide the new/existing customer question, and then reveal the relevant radio buttons for the option they choose.

2. Inconsistency

Non-standard GUI controls are a special case of the general problem of inconsistent design.

Confusion results when applications use different words or commands for the same thing, or when they use the same word for multiple concepts in different parts of the application.

Similarly, users are confused when things move around, violating display inertia.

Using the same name for the same thing in the same place makes things easy.

Remember the double-D rule: differences are difficult.

Another example from our current study: Expedia pops up a two-month calendar view when users specify the departure or return date for a trip. The composite screenshot below was taken in February and shows what happens when you want to book a trip that starts on March 10 and ends on March 15.

In the second pop-up, the month of March has moved to the left, leaving room for April to appear on the right. This may seem like a convenient shortcut, since there’s no way the user would want a February return date when traveling out in March.

In reality, however, the user is looking for March 15 in the same spot where it appeared in the first pop-up calendar: in the right-most column.

In our testing, the inconsistent placement of the months in the second pop-up caused confusion and delays, but users ultimately figured it out. We tested only a few users with this site, but if you observe this kind of almost-miss error in user testing, it’s usually a sign that a few users will make the mistake for real during actual use.

Booking the wrong return date can have disastrous consequences – customers could arrive at the airport without a ticket for their expected flight. If a site has good confirmation emails, users might discover the problem before departure, but even that will cause aggravation and expensive customer support calls to resolve the situation.

Even if people eventually use the calendar correctly, it takes more time to ponder the inconsistent design than the time users save by not having to click the next-month button for April departures.

The shortcut that moves the months around saves time only for very frequent users who learn how to efficiently operate this part of the UI. So, an application for professional travel agents should probably use Expedia’s calendar design. A site targeting average consumers should not.

3. No Perceived Affordance

“Affordance” means what you can do to an object. For example, a checkbox affords turning on and off, and a slider affords moving up or down. “Perceived affordances” are actions you understand just by looking at the object, before you start using it (or feeling it, if it’s a physical device rather than an on-screen UI element). All of this is discussed in Don Norman’s book The Design of Everyday Things.

Perceived affordances are especially important in UI design, because all screen pixels afford clicking – even though nothing usually happens if you click. There are so many visible things on a computer screen that users don’t have time for a mine sweeping game, clicking around hoping to find something actionable. (Exception: small children sometimes like to explore screens by clicking around.)

Drag-and-drop designs are often the worst offenders when it’s not apparent that something can be dragged or where something can be dropped. (Or what will happen if you do drag or drop.) In contrast, simple checkboxes and command buttons usually make it painfully obvious what you can click.

Common symptoms of the lack of perceived affordances are:

Users say, “What do I do here?”

Users don’t go near a feature that would help them.

A profusion of screen text tries to overcome these two problems. (Even worse are verbose, multi-stage instructions that disappear after you perform the first of several actions.)

When I tested some of the first Macintosh applications in the mid-1980s, users were often stumped by the empty screen that appeared when they launched, say, MacWrite. What do I do here, indeed. The first step was supposed to be to create a new document, but that command was not shown anywhere in the otherwise highly visible Macintosh UI unless you happened to pull down the File menu. Later application releases opened up with a blank document on the screen, complete with an inviting, blinking insertion point that provided the perceived affordance for “start typing.”

3.a. Tiny Click Targets

An associated problem here is click targets that are so small that users miss and click outside the active area. Even if they originally perceived the associated affordance correctly, users often change their mind and start believing that something isn’t actionable because they think they clicked it and nothing happened.

(Small click zones are a particular problem for old users and users with motor skill disabilities.)

4. No Feedback

One of the most basic guidelines for improving a dialog’s usability is to provide feedback:

Show users the system’s current state.

Tell users how their commands have been interpreted.

Tell users what’s happening.

Sites that keep quiet leave users guessing. Often, they guess wrong.

(For an example of the problems with poor feedback, see the screenshot of VW’s car configurator toward the bottom of my recent article reporting on our current round of testing: Because users couldn’t tell which tire was selected, they had trouble designing their preferred car.)

4.a. Out to Lunch Without a Progress Indicator

A variant on lack of feedback is when a system fails to notify users that it’s taking a long time to complete an action. Users often think that the application is broken, or they start clicking on new actions.

If you can’t meet the recommended response time limits, say so, and keep users informed about what’s going on:

If a command takes more than 1 second, show the “busy” cursor. This tells users to hold their horses and not click on anything else until the normal cursor returns.

If a command takes more than 10 seconds, put up an explicit progress bar, preferably as a percent-done indicator (unless you truly can’t predict how much work is left until the operation is done).

5. Bad Error Messages

Error messages are a special form of feedback: they tell users that something has gone wrong. We’ve known the guidelines for error messages for almost 30 years, and yet many applications still violate them.

The most common guideline violation is when an error message simply says something is wrong, without explaining why and how the user can fix the problem. Such messages leave users stranded.

Informative error messages not only help users fix their current problems, they can also serve as a teachable moment. Typically, users won’t invest time in reading and learning about features, but they will spend the time to understand an error situation if you explain it clearly, because they want to overcome the error.

On the Web, there’s a second common problem with error messages: people overlook them on most Web pages because they’re buried in masses of junk. Obviously, having simpler pages is one way to alleviate this problem, but it’s also necessary to make error messages more prominent in Web-based UIs.

6. Asking for the Same Info Twice

Users shouldn’t have to enter the same information more than once. After all, computers are pretty good at remembering data. The only reason users have to repeat themselves is because programmers get lazy and don’t transfer the answers from one part of the app to another.

7. No Default Values

Defaults help users in many ways. Most importantly, defaults can:

speed up the interaction by freeing users from having to specify a value if the default is acceptable;

teach, by example, the type of answer that is appropriate for the question; and direct novice users toward a safe or common outcome, by letting them accept the default if they don’t know what else to do.

Because I used Liste Rouge Paris as a bad example under Mistake #1a, I thought I’d play nice and use them as a good example here. The tailor offers 15 different collar styles (among many other options) for people ordering custom-designed shirts. Luckily, they also provide good defaults for each of the many choices. In testing, this proved helpful to our first-time user, because the defaults steered him toward the most common or appropriate options when he didn’t have a particular preference.

8. Dumping Users into the App

Most Web-based applications are ephemeral applications that users encounter as a by-product of their surfing. Even if users deliberately seek out a new app, they often approach it without a conceptual model of how it works. People don’t know the workflow or the steps, they don’t know the expected outcome, and they don’t know the basic concepts that they’ll be manipulating.

For traditional applications, this is less of a problem. Even if someone has never used PowerPoint, they’ve probably seen a slide presentation. Thus, a new PowerPoint user will typically have at least a bare-bones understanding of the application before double-clicking the icon for the first time.

For mission-critical applications, you can often assume that most users have tried the app many times before. You can also often assume that new users will get some training before seeing the UI on their own. At the minimum, they’ll usually have nearby colleagues who can give them a few pointers on the basics. And a good boss will give new hires some background info as to why they’re being asked to use the application and what they’re supposed to accomplish with it.

Sadly, none of these aides to understanding apply for most Web-based applications. They don’t even apply for many ephemeral intranet applications.

Usability suffers when users are dumped directly into an application’s guts without any set-up to give them an idea of what’s going to happen. Unfortunately, most users won’t read a lot of upfront instructions, so you might have to offer them in a short bulleted list or through a single image that lets them grok the application’s main point in one view.

As an example, our test user who was trying to order a custom-tailored shirt was highly confused when the first screen in Hamilton Shirts’ “Create Your Shirt” process displayed a fully designed shirt with an “Add to Bag” button. This screen mixed two metaphors: a configurator and an e-commerce product screen.

This is a case where a default value isn’t helpful: people who want to design their own shirt are unlikely to want to buy a pre-designed shirt on the first screen.

(This screen also suffers from Mistake #1: non-standard GUI controls. In addition to its non-standard drop-down selection menus in a tabbed dialog that doesn’t look enough like tabs, the screen has a non-standard way of paging through additional fabric swatches. Users are less likely to understand how to select fabrics when the controls are presented in this manner.)

Our test user never understood the process of designing his own shirt on this site and ultimately took his business elsewhere.

9. Not Indicating How Info Will Be Used

The worst instance of forcing users through a workflow without making the outcome clear is worth singling out as a separate mistake: Asking users to enter information without telling them what you’ll use it for.

A classic example is the “nickname” field in the registration process for a bulletin board application. Many users don’t realize the nickname will be used to identify them in their postings for the rest of eternity – so they often enter something inappropriate.

As another example, we once tested an e-commerce site that smacked users with a demand for their ZIP code before they could view product pages. This was a big turn-off and many users left the site due to privacy concerns. People hate snoopy sites. An alternative design worked much better: It explained that the site needed to know the user’s location so it could state shipping charges for the very heavy products in question.

10. System-Centric Features

Too many applications expose their dirty laundry, offering features that reflect the system’s internal view of the data rather than users’ understanding of the problem space.

In our current study, one user wanted to reallocate her retirement savings among various investments offered by her company’s plan (for example, to invest more in bonds and less in stocks). She thought she did this correctly, but in fact she had changed only the allocation of future additions to her retirement account. Her existing investments remained unchanged.

As far as the mutual funds company is concerned, new investments and current investments are treated differently. Reallocating future additions means changing the funds they’ll buy when the employer transfers money into the account. Reallocating current investments means selling some of the holdings in existing mutual funds and using the proceeds to buy into other funds.

The key insights here?

Our test user didn’t have this distinction between new and old money; she simply wanted her retirement savings allocated according to her revised investment strategy.

Even users who understand the distinction between new and old money might prefer to treat their retirement savings as a single unit rather than make separate decisions (and issue separate commands) for the new and old money.

It would probably be better to offer a prominent feature for changing the entire account’s allocation, and use progressive disclosure to reveal expert settings for users who want to make the more detailed distinction between the two classes of money.

Bonus Mistake: Reset Button on Web Forms

This mistake relates to Web forms, but because so many applications are rich in forms, I’ll mention it here: It’s almost always wrong to have a Reset button on a Web form.

The reset button clears the user’s entire input and returns the form to its pristine state. Users would want that only if they’re repeatedly completing the same form with completely different data, which almost never happens on websites. (Call center operators are a different matter.)

Making it easy for users to destroy their work in a single click violates one of the most basic usability principles, which is to respect and protect the user’s work at almost any cost.

(That’s why you need confirmation dialogs for the most destructive actions.) ( Source: useit.com)