总结现代电子游戏设计的50大创新理念

作者:Ernest Adams

从游戏玩法到游戏描述再到输入设备,电子游戏都可以称得上是孕育着创新理念的温床。我记录下了50种游戏设计创新理念,这些有的已经发挥作用了,而剩下的也必将在不久的未来大放异彩。

50年前,William Higinbotham创造了第一款基于示波器以及模拟电路的电子游戏。从那时开始,游戏便发生了巨大的变化,甚至是今天的AAA级游戏巨作也应该将自己的成功归功于早前的设计创新。我将在这篇文章中列举出50条我认为非常重要,或者将在不久后的某一天得到证实的游戏设计理念。这些理念中的很多方面都是早前游戏形式不断完善并增强的产物,就像体育,赛车以及射击等游戏也就是过去的露天比赛以及投币游戏的升级。而其它类型,如回合制策略游戏,逻辑智力游戏,角色扮演游戏等也都是从桌面游戏上慢慢发展而来。我们通过不同的方法去完善早前的游戏,而电脑也帮助我们能够创造出更多新类型的游戏,这也是其它媒体不能做到的。

不幸的是,我们经常会忽略掉那些游戏设计理念真正的创新者,反倒是那些运用了这些创新理念的游戏获得了这项殊荣。举个例子来说,大多数人只记得游戏《Pong》,但却不知道Ralph Baer(游戏邦注:电玩游戏之父)针对于奥德赛(游戏邦注:Magnavox Odyssey,全球第一款电子游戏机)创造的非电脑设计理念,尽管Baer的作品最先问世。为了纠正这种趋势,我将同时列出各个理念的最早提出者(如果能找到的话)以及早期最出名的创新典例(游戏邦注:作者并不能保证所有观点都是对的,但欢迎他人为其纠错)。

游戏玩法创新

我这里所说的游戏设置是指游戏提供给玩家的挑战,以及玩家为了应对这些挑战所采取的行动。绝大部分的行动都是很明显,如跳跃,驾驶,打斗,建造,贸易等等。但是也有一些挑战和行动比目前的游戏水平更先进,也为我们的游戏提供了一种全新的玩法。

1.探索

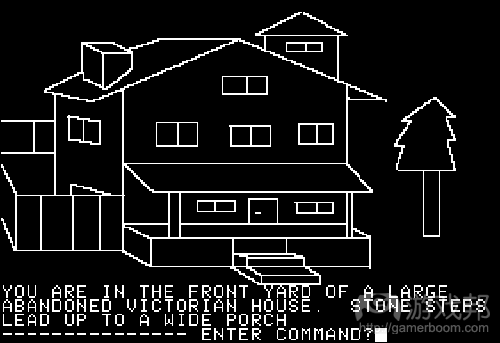

早前的电脑游戏并未提供给玩家探索机制。很多游戏只是在一个特定的位置安插一些模拟器,或者只是在较小的空间范围里提供一定的运动(如1972年的《Hunt the Wumpus》)。我们最后借鉴了桌面角色扮演游戏中的探索机制,并利用它们而创造出一些华丽大作,如《生化奇兵》等。真正的探索机制能够让你在进入一个不熟悉的地方时感到一种新奇感,并且你能够根据周边环境而做出一定的选择。这是与战斗完全不一样的挑战,能够吸引那些来自于现实世界的玩家们的注意。首次使用这个理念的游戏是《Colossal Cave》亦称作《Adventure》,发行于1975年。

2.讲故事

比起电子游戏的其它设计机制,讲故事更加备受争议,甚至有人还牵扯上了游戏保存的问题。我们是否应该这么做,或者我们应该怎么做?讲故事意味着什么?是否对游戏有所帮助?等等。

结果:并不是每一款游戏都需要故事,但是我们却不能不忽视它的存在。如果缺少故事,游戏将只能是一种抽象的存在,虽然能够吸引玩家的注意,但是这种吸引力却不再长久。我们经常认为首次使用讲故事机制的游戏是《Colossal Cave》,但是说实在的,这款游戏中并不存在着情节,而只是围绕着探索财宝展开。所以我认为首次使用讲故事理念的游戏是《Akalabeth》(游戏邦注:后来正式命名为《创世纪》,是该系列游戏的先驱之作),或者《Mystery House》,这两款游戏都发行于1980年。

3.秘密行动

事实上,绝大部分动作类游戏都是关于武力。甚至是当你面对的是一群力量强大的敌人时,你的唯一选择便是避开他们的绝招,想办法逃离他们或者找出他们最致命的弱点。秘密行动的游戏理念是指玩家必须想办法让敌人找不到他们,而这与《Rambo》这种硬碰硬的游戏类型完全不同。早前最有名的例子:1998年发行的《Thief: The Dark Project》。首次使用:不详。

4.拥有独立个性的游戏角色

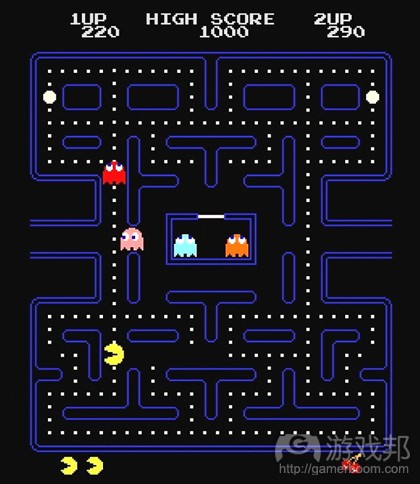

如果你对早期游戏年代并不熟悉,那么你必会对此感到惊讶。最初的探险类游戏以及其它电脑游戏都为玩家呈现了一个不一样的游戏世界,即在此,游戏角色不再只是你的代表物,而是真正的你。结果,游戏不再为你拟定年龄,性别以及社交地位等内容,因为使用这些虚拟的内容与游戏中的非玩家控制角色进行交流着实无聊透顶。早期的电子游戏经常只会出现一些车(如《Asteroids》,《太空入侵者》),甚至没有任何游戏角色(如《Pong》或者《夜之车手》)。拥有独立个性的游戏角色要求玩家必须证明自己有别于他人的特点,但是他们经常会随着游戏的进行而慢慢壮大发展。早前最有名的例子:《吃豆人》,发行于1980年(如果说是个性的话,那么发行于1981年的《大金刚》中的Jumpman,亦称为Mario也属于这种类型)。首次这种理念的可能是欧美游戏公司Midway在1975年发行的投币游戏的《枪战》。

5.领导权

在绝大多数党派争斗类角色扮演游戏以及射击类游戏,如《Ghost Recon》中,玩家可以单独控制一些游戏角色,但是却并未拥有领导权。关于领导权的真正挑战取决于其他玩家对你的违抗,特别是当你不得不接管一个团队,而毫无反抗能力之时。你可以通过你所控制团队成员完成任务的情况去判断他们的优劣,而判断他们的特性和能力则成为你需要掌握的一个必要技巧。一个较为鲜为人知,但是却真正典型的例子是1999年的《龙城之王》。而早前较为有名的例子便是1996年的《近距离作战》。首次使用:不详。

6.交际手段

对于电脑游戏来说这并不是一个特别新的理念,桌面游戏《强权外交》早在1959年便问世了。对于电脑来说,其面对的最大问题便是如何制作出最适合的AI,而如今我们也开始慢慢掌握这种方法了。拥有领导权的玩家便能够使用交际手段去判断其他角色,而非算计着如何对他们发动进攻。早前最出名的例子:1991年的《文明》。可能的首次使用:1986年的《Balance of Power》。

7.Mod支持(通过修改游戏代码来改变游戏的相关设置)

Mod是一种与角色扮演游戏一样具有创造性的玩法。早前的游戏并不具备可修改性,它们都属于开源内容,它们的源代码都会被刊登在诸如《Creative Computing》的杂志中。当我们开始贩售电脑游戏时,这些游戏的代码便开始成为了商业机密。所以在商业游戏中使用Mod着实是个非常大的进步,因为它大大扩展了游戏对于引擎的需求,而不再只让玩家受限于藏在小盒子里的游戏内容。早前最出名的例子:1993年发行的《毁灭战士》。可能的首次使用:1982年的《街机》,这款游戏的出现确立了塔防类游戏的基本结构。也许纯化论者会质疑固定操作模式的游戏能否称之为Mod游戏,但是关键在于这些游戏让玩家能够自己创造内容——而这都出现在“Web 2.0”或者“Web”之前。

8.有思想有意识的聪明NPC角色

在早前回合制2D游戏《Chase》中,你被囚禁在一个布满电丝网的笼子中,而且不断出现机器人试图要杀了你。所有机器人都在逼近你。如果你躲在电丝网后面,那么这些机器人便会走进去随之被炸个片甲不留,这就是10年前NPC角色的智力。随后我们便开始开发一些带有视觉和听觉的游戏角色,但是还是存在一定的限制因素。我们同样也开始赋予一些机器形式的角色智力,甚至是协作能力。现在最复杂的NPC角色AI出现在体育类游戏中,在此运动员必须为了获得集体目标而动作一致。我认为这是一种设计特征,由设计者提出并由程序人员想出如何在游戏中落实行动。首次使用:不详。

9.对话框

以前的电脑游戏中几乎没有用来做交流的对话空间。文本中的统一语法内容只能说是一种命令形式(如“把甜甜圈交给警察”),而非自然的讲话形式(“嘿,先生,你知道这附近哪里可以买到牙齿+5的护身符?”)。如果在游戏中安插了对话框,那么你便可以选择向其他角色表达自己的想法,而他们也会适时地对你做出回应。如果游戏允许的话,你可以进行“角色扮演”,也就是你可以用自己想要表达的态度去进行这种对话。如果编写妥当,脚本对话框也可以很自然地表现出游戏角色间的对话,也可以很有趣,形象生动。《Monkey Island》中因为受到侮辱而掀起的刀剑之争便是使用了这种对话框的功能。首次使用:不详。

10.多级别的游戏设置

通常来说桌面游戏都是围绕着同一种模式展开,或垄断或冒险。电脑游戏(以及桌面角色扮演游戏)则经常能让玩家在不同模式间发生转变,即可以从高级别的策略转变到低级别战术中。只有电脑能够让你在游戏中的不同级别之间进进出出,就像游戏《孢子》。你是否是一个围观管理者或者是精通于策略而不会为了一些琐事费神的人?不同游戏要求你使用不同的应对方法。早前最有名的例子:1983年发行的《Archon: The Light and the Dark》。首次使用:不详。

11.迷你游戏

指的是大型游戏中的一些小游戏,玩家可以自行选择要不要玩这些游戏。与多级别的游戏设置不同,这些小游戏与整体游戏也存在着很大的差别。《WarioWare》就是由这种迷你游戏组成的。也许很多时候迷你游戏会破坏玩家的沉浸式感受,但是同时也能够让他们在游戏中尝试一些不一样的体验。有时候这种迷你游戏甚至比整体游戏还优秀。首次使用:不详。

12.多种难度设置

游戏设计师John Harris曾经发现早前的游戏,特别是投币游戏都注重于测试玩家的技巧,而如今有一种更新的方法,便是无需测量玩家的技巧级别便提供给他们游戏体验。守旧派认为玩家是设计者的敌人,而先进派则认为玩家是游戏的观众。通过提供给玩家多种难度级别的选择,我们可以让游戏吸引到更多不同玩家的注意,同样也包括那些并不是那么擅长游戏的玩家。首次使用:不详。

13.逆转时间

拯救和再次加载游戏其实是相同的,但是有时候你想要的是毫无代价(游戏邦注:既无需重新加载游戏也无需回到前面的游戏步骤中)地纠正错误。最出名的例子:2003年发行的《波斯王子:时之沙》。在这款游戏中,玩家可以在每次犯错误的时候逆转时间10秒钟,但是为了阻止玩家不断使用这一方法,游戏规定每次玩家使用这种方法便要扣除一定量的沙子,而通过打败更多敌人才能弥补这些损失沙子。同时这款游戏还让玩家能够看到未来,从而帮助他们理解一些即将到来的疑惑,这也是游戏另一个让人佩服的创新之处。具有可能性的首次使用:2002年发行的《Blinx: The Time Sweeper》,玩家通过收集各种各样的晶体从而获得多次“一次性”的时间控制权。

14.双重身份的角色

这个创新有点新奇,玩家在游戏中的行动或者进行的任何冒险都可以通过使用两个特长不同,但可互补的游戏角色。有时候它们会相互协作一起行动,有时候玩家却不得不选择其中之一。但这与《Sonic and Tails》中两个完全不同的游戏角色不同。可能的首次使用:1998年发行的《Banjo-Kazooie》。

15.沙盒模式

这个特别的术语指的是玩家可以在游戏世界中到处晃荡而无需完成任何特定目标。至今为止最有名的沙盒模式游戏要数《侠盗猎车手》,这款游戏确实很受欢迎。沙盒模式是用来描写一种特别的游戏模式,即目标指向,而非《模拟城市》这种开放式游戏。有时候沙盒模式也可以用来应对游戏中一些突发行为或事件,这是游戏设计者未曾计划或预见到的。首次使用:不详。

16.物理谜题

很多现实世界的游戏都包含了物理性质,但是事实上它们只是简单地在测试玩家的技巧。而有了电脑我们便能够创造物理谜题,让玩家尝试着利用模拟目标的物理性质去解决问题完成目标。这是以智能而言,无需手和眼的调和。可能的首次使用:1992年发行的《不可思议的机器》。

17.交互式情节

也许现在只有部分游戏拥有这一机制,但是我相信在不久的将来一定会有更多游戏受益于这一机制。《Fa?ade》是一款第一人称3D游戏,发行于2005年。在游戏中你要想办法帮一对面临婚姻困境的夫妻解决问题。你在一个夜晚拜访他们,并在键盘上打出一些真实的句子与他们交流,而他们会以记录好的音频模式回复你。他们是否能够复合都取决于你所说的每一句话,也就是说你将深刻影响这对夫妻之间的关系——让他们复合,或者让其中一方离开,甚至是惹恼他们而把你提出家门。这是一个具有真实意义的角色扮演游戏:没有算计,没有战斗,没有财富,而只是一种带有情节式的互动——关于一对饱受婚姻折磨的夫妻未来的幸福。有很多设计师都认为《星际迷航:下一代》中的“全息剧”是交互式情节的“圣杯”。《Façade》在这一方面的探索着实是个大发展。

输入设备的创新

交互性是游戏中非常必要的一方面,特别是在电子游戏中,有些设备还将玩家的目的转化成实际行动。我们有按钮,把手(也可以说是转盘或浆),操纵杆,滑块,触发器,方向盘以及踏板。但是最近,我们关于输入设备的选择更加多样化了,甚至是一名非常优秀的设计者在选择输入设备前都要再三考虑而做出选择。

18.独立的移动和目标输入设置

早前的游戏总是要求游戏角色朝着一个特定的方向进行射击,就像《Asteroids》。如果区分了不同目标移动,那么游戏便需要使用两个操纵杆,而这就更加需要玩家去提高自己的物理协调性,但是这么做对于玩家和设计者来说都会比较自由。可能的首次使用:1982年发行的投币游戏《Robotron: 2084》。

19.指向-点击

鼠标的出现改变了玩家与空间以及立体物体间的交互方式。尽管在现在看起来有些过时,但是正是指向-点击机制让冒险类游戏比起早前基于分析系统去猜测“玩家动作”的游戏易亲近多了。早前最有名的例子:发行于1987年的《疯狂豪宅》;它所使用的SCUMM引擎直到现在仍然受到许多独立开发者的喜欢。可能的首次使用:1984年发行的针对于Macintosh(游戏邦注:苹果公司于1984年推出的一种系列微机)的游戏《Enchanted Scepters》。苹果Mac是第一款带鼠标的个人电脑。

20.使用鼠标+方向键控制的第一人称3D移动方式

在我们发明出虚拟现实操控装置之前,鼠标和方向键可谓是3D空间中用来控制第一人称角色的最佳方法。甚至是控制器上的双游戏摇杆也无法做到如此精确。首次使用:不详。

21.语音识别(及其它扩音器的支持)

高声大喊“A伙计,开火!”或者用鼠标在A伙伴周围画一个框框,然后点击菜单选项中的“开枪”,这两种方法那个比较刺激?朝着好友(或者敌人)大喊,亦或是与他们一起唱歌都属于游戏中一大乐趣。可能的首次使用:发行于1987年的发行于Commodore 64型主机上的《空中梯队》。

22.针对音乐的专业I/O设备(并不包括MIDI键盘)

不论是技术还是设计,I/O设备中的进步都能够帮助我们改变游戏的玩法,特别是针对于音乐类游戏而言。音乐和舞蹈对于物理活动的要求都很高,所以很难在操纵杆或者键盘上表现出来。

《吉他英雄》的控制器能够表现出沙球,康茄鼓等乐曲演奏的音乐,所以非常有趣。可能的首次使用:发行于1998年的《劲舞革命》跳舞毯。

23.手势接口

有一些文化都赋予了手势一些特殊且具有象征意义的能量,从天主教徒的双手合十到印度教的马德拉舞再到佛教的造像,我们都可以看到特殊手势的体现。手势也总与魔法联系在一起,魔杖就是其中一部分。而在一些电子游戏中玩家只能通过点击标识按压按钮去施展魔法,如此看来并不能带来多大感受吧。手势接口是最近刚刚发明的一种方式,即让玩家能够不使用语言和技术方法便能够表达自己。最出名的例子:任天堂的控制器。可能的首次使用:发行于2001年的《黑与白》。

24.可重组的控制以及其它易用性功能

当你习惯了一款游戏的控制器以及键盘设置后,你肯定也会希望能够按照相同的操纵方式去玩其它类似的游戏。现在的电脑游戏让玩家能够重新设置自己键盘的操作键位,但是在掌机设备中却还未普及这一做法。这一方法对于那些残障人士来说至关重要。不幸的是,很多游戏设计者都忽视了那些残疾人士的游戏需求,这点着实让我感到可耻。而我们现在开始慢慢了解到这个现实了。其它一些有意义的创新包括:为听觉有问题的玩家提供字幕选项;区分音乐的音量控制和音效;设置可调节的亮度和对比度;为色盲玩家设置可选择的调色板;以及可设置的游戏速度等等。对于易用性游戏设计来说,“天下没有游戏速度太慢这回事”。

呈现方式的创新

在玩家的视觉和听觉方面进行创新需要依靠大量先进技术,而我也仍认为这也是一种设计创新,是游戏设计者所选择的并用于(或者没有)其游戏中的特殊功能。静态以及轴卷式2D屏幕就是如此,而且早在之前的投币游戏时期它们便存在了。

25.等角视角,有时候也称“四分之三视角”

在侧面视角和顶端视角控制着电子游戏多年后,等角视角一出现便让人惊艳连连。它所创造的立体感是当时游戏所缺少的。它的出现让玩家能够很自然地同时看到一个物体的顶端和侧面,而无需通过任何尴尬的“欺骗”方式;甚至还可以转动这个物体以观察它的其它方面(如果设计者提供了这一功能的话)。早前最有名的例子:发行于1989年的《上帝也疯狂》。可能的首次使用:发行于1982年的投币游戏《立体空战》。

26.第一人称视角

第一人称视角比起其它视角更为直接。当敌人拿着枪杆指向你的时候,你便能真切地体会到枪杆就在面前的紧张感。但是最大的代价便是你看不到自己角色的正面。第一人称并不等价于3D;在最早的例子中,主角并不能够完成3D移动或者上窜下跳。早前最有名的例子:发行于1980年的投币游戏《终极战区》。可能的首次使用:1973年用NASA(美国国家航空和宇宙航行局)中的Imlac小型计算机开发的《迷宫战争》。

27.第三人称视角

从游戏角色后面,即越过他的肩膀这个方位去控制他。摄影机将随时跟随游戏角色行走。与第一人称一样,第三人称也不需要真正的3D空间,但是它所提供的画面却与之类似。这种创新非常重要,因为它让玩家按照一种较为自然的角度去观看自己的角色如何做事,而不像早前的横向或滚动式视角。但是这种代价便是,你的游戏角色可能会遮住游戏中的一些部分,而这点在射击游戏中就非常不利。早前最有名的游戏:发行于1996年的《古墓丽影》。首次使用:不详。《Pole Position》(1982年)中一些跟随车辆的视角则更适合被定义为追随视角。

28.过场动画

不论你喜不喜欢,它们都是游戏场景中的一部分。它们能够让玩家在游戏中途获得一定的休息时间,让他们能够从另一个视角去观看游戏世界(而且往往是最吸引人的部分),当然了,通过过场动画游戏也能够阐述一个故事。早前最有名的游戏:发行于1987年的《疯狂豪宅》。可能的首次使用:发行于1979年的《吃豆人》。

29.真实3D

因为我们的CPU经常不足以提供真实的画面,所以我们经常会仿照一些类似于3D的视角。《毁灭战士》就是一款聪明地仿照了3D画面的游戏。3D并不一定能够改善游戏设置,如《疯狂小旅鼠》与《疯狂小旅鼠3D》,但是它带给游戏的影响确实非常巨大的。甚至连手机也开始加入3D加速器。早前最有名的例子:1982年发行的《微软模拟飞行X》V1.0版。可能的首次使用:发行于1974年的《SPASIM》,是一款以星际迷航为主题的多人主机游戏。因为这些游戏中的目标数量都很有限,所以都有可能创造出这种真实的3D效果。

30.情境摄像机

随着第三人称视角的出现,情境摄像机也紧随其脚步,慢慢贯穿于游戏中。情境摄像机让游戏设计者也能够使用电影摄影技师的技巧在最佳方位展现游戏最棒的角度。对于冒险游戏以及慢节奏的动作冒险游戏来说,情境摄像机再合适不过了。而在快节奏的游戏中,摄像机的突然移动都会让玩家失去方向感;所以为更好地操纵事件的速度,你需要一个可预见的视点。最受欢迎的例子:发行于2001年的《古堡迷踪》。首次使用:不详。但是,预渲染的背景(在指向与点击冒险游戏中)和玩家控制摄像机(就像《狩魔猎人3》)都与之不同。

31.程序上的场景生成

这种技巧让设计者无需动手便能够创造出大量的游戏空间。如果他们能够快速生成这些空间,甚至不用将其保存,这对于早期机器来说非常重要。早前最有名的例子:发行于1984年的《七座金城》。可能的首次使用:发行于1982年的《河上反击》。

32.可变化的对话回放

这指的是将一些音频剪辑汇聚在一起而制作一个富有多种内容的无缝对话。我们用这种方法去播放体育游戏中的详情内容,并且将不同运动员的名字都插入注释中。同时我们经常利用这种方法去创造犹如电视般的游戏体验。早前最受欢迎的例子:发行于1992年的《硬派棒球III》。可能的首次使用:1992年在CD-i播放器上的《3rd Degree》(歌曲)。

33.情景交融的音乐

每个人都知道音乐能够陶冶情操。在电子游戏中,音乐的变化是针对于不同游戏事件而做出回应,当然了,作曲家也不会知道音乐会在什么时候出现。一种简单的方法便是你可以在需要的时候插入一首新曲,但是如果过渡不好的话也许会适得其反。另外一个方法是层次化,你可以将不同类型的音乐混合在一起,改变它们的音量以适应游戏中的不同需要。早前最有名的例子:发行于1990年的《银河飞将》。可能的首次使用:1982年发行于Atari800上的《Way Out》。

34.子弹时间

飞行模拟器上的可调节时间早已成为另一种标准;它让你能够加速游戏世界中的时间从而能够更快地穿越一些乏味的阶段。子弹时间是后来的一种创新。它放缓了时间同时也让你能够快速行动,从而让你感受到一种超高速的体验,并伴随着一般游戏中的超强度以及超负荷的感觉。早前最有名的例子:发行于2001年的《英雄本色》。可能的首次使用:发行于1999年的《安魂曲:堕落天使》。

35.可变化的环境

这里我要提到一个传统游戏的谬论:一场大爆炸能够摧毁一辆坦克,但是却对附近的墙壁和窗户没有任何影响。而可变化的环境能够纠正这一谬论并让你逐渐改变游戏世界。这一功能对于游戏关卡的设计可能是一大挑战,因为玩家有可能会踏进设计者不喜欢他们进入的领域;但是它却能够让整个世界变得更加真实,而玩家也能够按照自己的方法去解决问题。可能的首次使用:发行于1994年的《魔毯》。

36.对于特殊属性的巧妙指示

健康,速度,魔法值,生命,弹药,燃料等等都是按照同一标准的指示器来表示:能量条,数字,计量表以及重复的小图像。许多都是借鉴于现实世界中的设备。那么那些比较不明显的属性又是怎样表达的呢?在过去的几年里,我们已经设置了一些较为巧妙的方法去表现它们,因为方法实在太多了,我就不好在此一一列举,所以我将它们综合在了一起。以下是我个人喜欢的一些方法:《黑暗计划》中的闪光灯能够暗示你的角色可能会被注意到;在射击游戏中,当瞄准器离得越远便意味着你的武器的准确度越低;而如果屏幕变模糊了或者出现了一些朦胧特效,那么你的游戏角色可能喝醉了或者被下药了。

类型

我们从其它游戏形式中借鉴了许多电子游戏的类型,但是有些类型只有在电脑出现之后才能得以发展,并展现出真正的设计创造性。

37.建设和管理模拟

乐高积木和商业管理游戏都先于电脑出现,但是正是电子游戏的出现才首次将这两种理念结合在了一起。早前最有名的例子:发行于1989年的《模拟城市》。可能的首次使用:1982年发行于美泰Intellivision主机上《乌托邦》。

38.即时战略游戏

回合制战争类游戏其实是跟源自一些传统游戏,如桌面游戏《Avalon Hill》,而且有很多回合制游戏与桌面游戏很相似,即有一些四方形的计量仪表以代表六角网格中的一些单位。而即时战略游戏则使得这类型游戏更容易被大众所接受,即使也有一些纯化论者抱怨即时战略游戏只是用快速的鼠标点击以及资源管理等方法去取代真正的策略游戏。早前最有名的例子:发行于1984年的《古代战争艺术》。可能的首次使用:1983年针对ZX Spectrum(游戏邦注:1982年由Sinclair公司生产的一款8位个人电脑)发行的《Stonkers》。与之相关的游戏类型是即时战术游戏,这种类型主要针对于个人战场(例如《全面战争》系列游戏)而取消了即时战略游戏中的资源管理方面。

39.格斗游戏

除了现实世界中的体育运动以及20世纪60年代的玩具“格斗机器人”,我找不到任何可以称得上是视频格斗游戏先驱的例子了。虽然很多游戏都带有格斗元素,但是真正的格斗游戏更加专注于混战而非探索或者解决谜题。格斗游戏已经远远超乎现实世界中的武术(其中更是涵括了魔力,虚构的武器以及一些非现实属性)而包含一些资深的创造性元素。虽然现在也出现了一些子类别,但是最普遍的游戏元素仍是不使用任何远程武器而进行空手搏斗。可能的首次使用:1976年发行的投币游戏《重量级冠军》。早前最受欢迎的例子:1987年发行的《街头霸王》。

40.节奏,舞蹈与音乐游戏

早在《Pong》那个时代就有了关于时间协调的游戏,但是针对于节奏的游戏直到最近才真正出现。如今关于制作音乐的游戏越来越受欢迎。而且因为这种游戏避免了反反复复的暴力冲突,所以更加受到女性玩家的喜欢。早前最受欢迎的例子:发行于1996年的《啪啦啪啦啪》。可能的首次使用:1995年的在世嘉32X游戏机上发行的《Tempo》。(发行于1984年的《音乐建筑合辑》,但是它并不算是一款游戏。)

41.模拟宠物和人类

人们总喜欢观看一些小动物如何生活,特别是当它们死后而无需对其感到内疚的时候(或者它们永远都不会死去)。训练,培养这些小东西,并购买饰品装饰它们就是一种乐趣。《模拟人生》一直是最畅销的电脑游戏;任天堂DS上的《任天狗》也是一款大热游戏。可能的首次使用:1985年发行的《电脑小人》。早前最受欢迎的例子:1995年发行的《模拟宠物狗》。

42.上帝游戏

这类型的游戏混合了建设,管理模拟,即时战略游戏,模拟类游戏以及其本身的一些特性。在上帝游戏中,你将扮演上帝的角色去控制一群人,而你的主要工作则是帮助他们变繁荣。在这里的主要功能是间接控制,你可以通过自己的行动去影响信仰者们,但是你却不能够直接向他们下达命令;同时你还拥有一些神圣的力量,如改变风景或者引发一些自然灾害等。上帝游戏让我们能够在需要的时候制造火山喷发,还有什么需要我说的呢?可能的首次使用:1989年发行的《上帝也疯狂》。(有些人认为1982年发行的《乌托邦》也属于上帝游戏,但是我却将其归类为内容管理游戏,因为在这里玩家的权利并不像上帝那般神圣。据说Firaxis公共关系部门也声称《文明》不属于上帝游戏。)

43.社交和约会游戏(包括或不包括性)

我只能找到一款非电脑的约会游戏,即Milton Bradley在1965年发行的桌面游戏《Mystery Date》。主要的电脑约会模拟游戏都是出自日本。在这种游戏中,多会出现对话框,而玩家则通过一些对白与自己期望的搭档拉近关系。有的约会游戏带有很复杂的属性系统,并不像是普通的角色扮演游戏,它们更倾向于描写角色的浪漫而非他们如何击败一个怪物。可能的首次使用:发行于1992年的《同级生》。

44.交互式电影

这种类型来了却又走了,真是可喜可贺。这可称得上是改变世界的设计创新,因为它把创造性带进了一个死胡同里,让每个人都发誓再也不会制作交互式电影了,尽管现在我们仍然能够在一些不同类型中看到这个术语对于其它游戏电影质量的描述。交互式电影给予了我们一个负面的例子,即游戏玩法最重要。CD驱动器的出现使得这种交互式电影成为了可能,而在它的全盛时期,甚至获得了巨大的销量。直到人们对于观看这种小东西的好奇和热情慢慢冷却。早前最受欢迎的例子:发行于1993年的《第七访客》。可能的首次使用:发行于1983年的投币游戏《龙穴历险记》。

45.“针对于女孩的游戏”(而非女人)

在游戏产业早期发展中可以说完全忽视了女孩玩家。在20世纪90年代中期,曾经出现了为女孩制作游戏的短暂热潮,但是这些游戏看起来就像是一些营销炒作,而很多女孩子都是被那些用粉色盒子包裹着的假冒产品所欺骗。这种为女孩制作游戏的理念在最近再次兴起了,如《贝兹娃娃》系列。但是对于这类型的游戏仍然有许多争议,有些人认为实现女孩对购物的幻想并不需要像实现男孩对暴力的幻想那样担负社会责任。而其它瞄准女孩市场的游戏也不再那么古板了,如《神秘南茜》冒险游戏。早前最受欢迎的例子:发行于1996年的《巴比时装设计师》,可能的首次使用:1991年的《芭比娃娃》。(尽管同样出现于1980年的《吃豆人》和《蜈蚣》都深受女性玩家的欢迎,但是它们却都未明确指向女孩玩家。而发行于1982年的《被俘之心》则更是针对于成年女性玩家。)

游戏风格

每个玩家的游戏风格都不一样,游戏设计者应该如何就此改进游戏。

46.吹牛榜单(或者说是高分排行榜)

早前的桌面游戏并没有排行榜。如果你是在玩多人游戏,那么你便可以和好友一决高下,但是结果却只有你们两人知晓。而吹牛榜单可以将你的名字首字母以及你的游戏成绩公开,让你始终高高在上,除非被更厉害的对手而打败。首次使用:1979年发行的《Asteroids》。

47.保存游戏

自从保存功能出现以来,便出现了对于这一目标的两种不同看法,有些人喜欢挑战一些复杂的环节而不需要任何安全措施,也有些人喜欢中途停止游戏并按照自己的时间安排表再次开始游戏。不论好坏,按照你自己的观点,保存游戏的能力都将深刻影响到你的游戏风格。保存游戏的方法多种多样,但是这些方法也有自己的优劣。我把关卡密码以及检查点集特归类于此。首次使用:年代太久远了已经无从考究。

48.调制解调器以及网络游戏

调制解调器让玩家们能够双双一起玩游戏。尽管这已经是非常重要的一大发展,但是最大的缺陷在于缺少适当的配对设备,即两个玩家必须同时拥有调制解调器并且进行相同一款游戏才行。

后来随着互联网逐渐普及,媒体的方式便越来越多样了。事实上,在个人电脑出现之前互联网便已经存在了。早前最受欢迎的例子:1986年发行于Commodore 64上的《杰克兔俱乐部》。可能的首次使用:1974年发行于Imlac小型计算机上的《迷宫战争》。

49.多人游戏地下城(MUD)

将游戏中的探索乐趣,如《魔域大冒险》与多人游戏的乐趣相结合,你便能够感受到多人游戏地下城的魅力。MUD可以说是今天大受欢迎的大型多人在线角色扮演游戏的先驱。在韩国,这种游戏甚至可以称得上是“国粹”。早前的MUD版本并非互联网游戏,而是运营于一些分时主机上的游戏。首次使用:于1979年在埃塞克斯大学问世的MUD。

50.派对游戏

虽然我们有了多人游戏,但是派对游戏与之还是有所区别,这种游戏主要是为了在一个模仿真实派对的情境下提供给玩家娱乐体验,而玩家可以在好友的陪同下享受派对的乐趣。比起让玩家沉浸于游戏中的虚幻世界,派对游戏更注重于提供各种迷你游戏而让玩家放松心情。首次使用:发行于1998年的《马里奥聚会》。

以上是我所选择的50大设计创新理念,我们已经见识到一些理念的重要性了,而剩下的必将在不久的将来发挥其作用。关于这些理念的重要性肯定存在着众多分歧,而且我们也许也忽略了一些重要的内容,所以我希望在不久的将来我们能够就此作进一步的讨论。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

50 GREATEST GAME DESIGN INNOVATIONS

From gameplay, to presentation to input devices, videogames are a hotbed of innovation. Ernest Adams notes 50 game design innovations, some that have already made their impact, and others that will shape the future of the medium…

Digg this article here.

Fifty years ago William Higinbotham built the first videogame with an oscilloscope and some analog circuitry. While games have changed enormously since then, even today’s AAA blockbusters owe some of their success to design innovations made years earlier. In this article I’m going to look at 50 design advances that I feel were especially important, or will prove to be some day. Many of them are actually enhancements to older forms of play; sports, driving, and shooting go back to fairground games and mechanical coin-ops. Other genres, such as turn-based strategy, logic puzzles, and RPGs, began life on the dining room table. We have improved these earlier games in many ways, and the computer has allowed us to create new genres that would be impossible in any other medium.

Unfortunately the true innovator of a design idea is often forgotten, while a particularly successful later game gets the credit. For example, more people remember Pong than remember Ralph Baer’s non-computerized design for the Magnavox Odyssey, even though Baer’s work came first. To correct this tendency, I’ll list both the original inventor of the idea (if I could find it) and the best-known early example of the innovation. I don’t promise to be right all the time; corrections are welcome.

Gameplay Innovations

By gameplay I mean the challenges that the game poses to the player, and the actions that the player may take to meet the challenges. The vast majority of these actions are obvious: jumping, steering, fighting, building, trading and so on. But some challenges and actions distinctly advanced the state of the art, and provided new ways for us to play.

1. Exploration.

The earliest computer games didn’t offer exploration. Many were simulations set in one location, or afforded movement only through trivial spaces (e.g. Hunt the Wumpus, 1972). We eventually borrowed exploration from tabletop role-playing and turned it into extravaganzas like BioShock. True exploration provides ongoing novelty as you enter unfamiliar areas, and lets you make choices based on clues in the environment. It’s a different sort of challenge from combat, and attracts players who enjoy being virtual tourists. Probable first use: Colossal Cave, aka Adventure, 1975.

2. Storytelling.

Storytelling is the subject of more acrimonious debate than any other design feature of videogames, even including the save-game issue. Should we do it or not, and if so, how? What does it mean? Is it even possible to do well? —and so on. Bottom line: not every game needs a story, but they’re here to stay. Without a story, a game is just an abstraction—which can be enough to engage the player, but isn’t always. First use is often attributed to Colossal Cave, but that was really a treasure-hunt without a plot. Possible first use: Akalabeth, precursor to the Ultima series, or Mystery House, both released in 1980.

3. Stealth.

Let’s face it, most action games are about force. Even when confronted with overwhelmingly powerful enemies, your only option is to avoid their killing shots while grinding away at them or searching for their vulnerable spots. In stealth play the idea is to never even let the enemies know you’re there, and it requires a completely different approach from the usual Rambo-style mayhem. Best-known early example: Thief: The Dark Project, 1998. First use: unknown.

4. Avatars with their own personalities.

If you weren’t around in the early days this one might surprise you. The first adventure games, and most other computer games too, described the world as if you, the player, were actually in the game—not a representation of you, but you. Consequently, the games could make no assumptions about your age, sex, social position, or anything else—which meant that NPC interactions with your avatar were always rather bland. The early video games, too, mostly displayed vehicles (Asteroids, Space Invaders) or no avatar at all (Pong, Night Driver). Avatars with independent personalities required you to identify with someone different from yourself, but they increased the dramatic possibilities in games enormously. Best-known early example: Pac-Man, 1980 (if you can call that a personality; otherwise, Jumpman, aka Mario, in Donkey Kong, 1981). Possible first use: Midway’s Gun Fight coin-op, 1975.

5. Leadership.

In most party-based RPGs and shooters like Ghost Recon, you can control any of the characters individually, but that’s not really leadership. The true challenge of leadership is delegating to others who might disobey you, especially when you have to take over an existing team without any choice about who’s in it. The strengths and weaknesses of your people determine how well they succeed at the tasks you give them, so judging their characters and abilities becomes a critical skill. A little-known but excellent example is King of Dragon Pass, 1999. Best-known early example: Close Combat, 1996. First use: unknown.

6. Diplomacy.

Not new with computer games—the board game Diplomacy was first published in 1959. The big problem for computers has always been making credible AI for computer opponents, but we’re starting to get this right. As with leadership, diplomacy is more about judgment of character than counting hit points. Best-known early example: Civilization, 1991. Probable first use: Balance of Power, 1986.

7. Mod support.

Modding is a form of gameplay; it’s creative play with the meta-game. The earliest games weren’t just moddable, they were open-source, since their source code was printed in magazines like Creative Computing. When we began to sell computer games, their code naturally became a trade secret. Opening commercial games up to modding was a brilliant move, as it extended the demand for a game engine far beyond what it would have been if players were limited to the content that came in the box.

Best-known early example: Doom, 1993. Probable first use: The Arcade Machine, 1982, which was a construction set for arcade-like games. Purists may debate whether construction set products count as moddable games, but the key point is that they enlisted the player to build content—long before “Web 2.0” or indeed the Web itself.

8. Smart NPCs with brains and senses.

In an early 2D turn-based game called Chase, you were trapped in a cage filled with electric fences and some robots trying to kill you. All the robots did was move towards you. If you could get behind an electric fence, they’d walk into it and fry—and that was the sum total of NPC intelligence for about ten years. Then we began to implement characters with vision and hearing and limits to both. We also gave them rudimentary brainpower in the form of finite state machines and, eventually, the ability to cooperate. Some of the most sophisticated NPC AI is now in sports games, where athletes have to work in concert to achieve a collective goal. I consider this a design feature, as it’s something designers asked for and programmers figured out how to implement. First use: unknown.

9. Dialog tree (scripted) conversations.

Early efforts to include interactive conversation in computer games were pretty dire. The parsers in text adventures were okay for commands (“GIVE DOUGHNUT TO COP”) but not for ordinary speech (“Hey, mister, do you know anybody around here who can sell me an Amulet of Improved Dentistry+5?”). With a dialog tree the game gives you a choice of pre-written lines to say, and the character you’re talking to responds appropriately. If the game allows it, you can role-play a bit by choosing the lines that most closely match the attitude you want to express. Written well, scripted conversations read like natural dialog and can be funny, dramatic, and even moving. The hilarious insult-driven sword fights in the Monkey Island games are sterling examples of the form. First use: unknown.

10. Multi-level gameplay.

With a board game everything usually takes place on the same board, as in Monopoly or Risk. Computer games (and tabletop RPGs) often let you switch between two modes, from high-level strategy to low-level tactics. And only a computer can let you zoom in and out to any level you want—as Spore apparently will do. Are you a micromanager or a master of strategy who doesn’t sweat the small stuff? Different games demand different approaches. Best-known early example: Archon: The Light and the Dark, 1983. First use: unknown.

11. Mini-games.

A small game within a big game, usually optional, sometimes not. Not the same as multi-level gameplay; a mini-game feels very different from its parent. WarioWare consists of nothing but mini-games. Mini-games often destroy the player’s immersion, but offer a different set of challenges from those in the overall game.

Sometimes the mini-game is actually better than the overall game. First use: unknown.

12. Multiple difficulty levels.

Designer John Harris has observed that older games, especially coin-ops, were intended to measure the player’s skill, while the newer approach is to provide the player with an experience regardless of his skill level. The old-fashioned school of thought is that the player is the designer’s opponent; the new school is that the player is your audience. By offering multiple difficulty levels, we make games available to larger audiences, which also includes handicapped players. First use: unknown.

13. Reversible time.

Saving and reloading is one thing, but sometimes what you really want is what as kids we used to call a “do-over”-a chance to correct an error without the hassle of a reload or going back a long way in the game world. Best-known example: Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, 2003. When you made a mistake, you could reverse time for ten seconds. To prevent you from using it continually, each usage costs you a certain amount of sand, which has to be replenished by defeating enemies. The game also let the player see into the future to help with upcoming puzzles, another clever innovation. Possible first use: Blinx: The Time Sweeper, 2002, in which collecting up crystals in various combinations gives the player a variety of one-shot time control commands.

14. Coupled avatars.

In this slightly oddball innovation, you play an action or action-adventure game using two quite different avatars with complementary abilities. Sometimes they work together as one; at other times you have to choose which to use, or are required to use one or the other. Not the same as two separate avatars like Sonic and Tails. Possible first use: Banjo-Kazooie, 1998.

15. Sandbox modes.

The term refers to a mode of play in which you can fool around in a game’s world without being required to meet a particular objective. By far the best-known sandbox modes are in the later Grand Theft Auto games, contributing greatly to their popularity. Sandbox mode is normally used to describe special modes within otherwise goal-oriented games, not open-ended games like SimCity. Sandbox modes also sometimes afford emergent behavior, events arising in a game’s world that were not planned or predicted by the designer. First use: unknown.

16. Physics puzzles.

Many real-world games involve physics, but they’re usually tests of skill. The computer lets us create physics puzzles, in which you try to figure out how to accomplish a task using the physical properties of simulated objects. They’re about brainpower, not hand-eye coordination. Possible first use: The Incredible Machine, 1992.

17. Interactive drama.

There’s only one of these, but someday its descendants will change the world. Fa?ade is a first-person 3D game released in 2005. In Fa?ade you play the friend of a couple whose marriage is in trouble. You visit their apartment for an evening and converse with them by typing real English sentences; they respond with recorded audio. Depending on what you say, you can influence their relationship—get them to reconcile, cause one or the other to leave, or even anger them so much that they throw you out. It’s role-playing in the real meaning of the term: no stats, no combat, no treasure, just dramatic interactions—with a couple’s future happiness at stake. Many designers consider the “holonovels” from Star Trek: The Next Generation to be the holy grail of interactive storytelling; Fa?ade is an important advance on the quest.

Input Innovations

Interactivity is the essence of gaming, and in a videogame, some device has to translate the player’s intentions into action. We’ve always had buttons, knobs (aka spinners or paddles), joysticks, sliders, triggers, steering wheels and pedals. But recently our options for input devices have exploded, and a good designer gives careful thought to them before choosing an approach to use.

18. Independent movement and aiming.

Early games restricted the avatar to shooting in the direction that it was facing—as in Asteroids, for example. Separating movement from aiming requires a second joystick, which substantially increases the physical coordination required of the player, but offers more freedom for both player and designer. Probable first use: Robotron: 2084 coin-op, 1982.

19. Point-and-click.

The mouse changed the way players interact with spaces and the objects within them. Although now considered dated, point-and-click made adventure games much more accessible than the older “guess the verb” parser-based system. Best-known early example: Maniac Mansion, 1987; the SCUMM engine devised for it is still in use by independent developers. Probable first use: Enchanted Scepters for the Macintosh, 1984. The Mac was the first personal computer to routinely ship with a mouse.

20. Mouse+WASD keys for 3D first-person movement.

This is so much the best way to move a first-person avatar in a 3D space that, until we get virtual reality gear that really works, there is no reason to consider anything else. Dual-joystick setups on controllers can’t match it for precision. First use: unknown.

21. Speech recognition (and other microphone support).

Which is the more exciting: yelling “Company A, charge!” or drawing a box with your mouse around Company A, then clicking a menu item labeled CHARGE? I rest my case. And hollering at your buddies (or at your enemies)—or singing with them—can be a big part of the fun too. Probable first use: Echelon for Commodore 64, 1987.

22. Specialized I/O devices for music (not counting MIDI keyboards).

Part technology, part design, advancements in I/O devices have changed the way we play, especially in musical games. Making music and dancing to it is an intensely physical activity that doesn’t easily translate to joysticks and typewriter keyboards. Maracas, conga drums, the Guitar Hero controller—all great fun. Possible first use: dance mats in Dance Dance Revolution, 1998.

23. Gestural interfaces.

Many cultures imbue gestures with supernatural or symbolic power, from Catholics crossing themselves to the mudras of Hindu and Buddhist iconography. Magic is often invoked with gestures, too—that’s part of what magic wands are for. The problem with a lot of videogame magic is that clicking icons and pushing buttons feels more technical than magical. The gestural interface is a comparatively recent invention that gives us a non-verbal, non-technical way to express ourselves. Best-known example: Wii controller. Probable first use: Black & White, 2001.

24. Reconfigurable controls and other accessibility features.

When you get used to a certain controller or keyboard setup, you want to be able to use it in every analogous game. PC games now routinely allow players to remap the commands on their input devices, but this is not yet as common as it should be on console machines. For people with hand problems it can be vital. Unfortunately, game developers have almost completely ignored the needs of the handicapped—to our lasting shame. We’re finally starting to get a clue. Among the other useful innovations here are: subtitles for the hearing-impaired; separate volume controls for music and sound effects; adjustable brightness and contrast controls; alternative color palettes to help the color-blind; settable game speed. The slogan of accessible game design is there’s no such thing as “too slow.”

Next: Presentational innovations

MOSPAGEBREAK

Presentational Innovations

Innovations in what the player sees and hears may depend heavily on technological advances, but I still consider them design innovations as well, features the designer can choose to use in their game—or not. I take static and scrolling 2D screens for granted; they already existed in mechanical coin-ops.

25. Isometric perspective, also sometimes called “three-quarters perspective.”

After years of side-view or top-view videogames, the isometric perspective provoked gasps of astonishment when it first appeared. It created a sense of three-dimensionality that had been sorely lacking from games to that point. For the first time, players could see both the tops and the sides of objects in a natural way, rather than through awkward “cheated” sprites, and could even move around objects to see them from the other side, if the designer had provided that feature. Best-known early example: Populous, 1989. Probable first use: Zaxxon coin-op, 1982.

26. First person perspective.

First person lends immediacy like no other point of view. When an enemy points a gun at you, it’s really at you—right in your face. The big tradeoff is that you don’t get to see your avatar, so visually dramatic activities such as traversing hand-over-hand along a telephone wire lose their impact. First person doesn’t have to mean true 3D; the earliest examples didn’t allow fully 3D movement or tilting up and down. Best-known early example: Battlezone coin-op, 1980. Probable first use: Maze Wars, developed at NASA on the Imlac minicomputer, 1973.

27. Third person perspective.

Controlling your avatar as seen from behind, looking over its shoulder. The camera follows wherever the avatar goes. Like first person, third person doesn’t necessarily require a true 3D space, but it has to seem like one. This innovation was important because it allowed you to watch a heroic character doing his stuff from a natural viewpoint, unlike the older side-scrolling and top-scrolling perspectives. The tradeoff is that the avatar obscures your view of part of the world, which can be awkward in shooting games. Best-known early example: Tomb Raider, 1996. First use: unknown. Viewpoints that follow vehicles as in Pole Position, 1982, are more properly defined as chase views.

28. Cut scenes.

Love ’em or hate ’em, they’re part of the gaming landscape. They give players a rest between periods of activity, allow them to see the game world from a viewpoint that doesn’t have to be playable (and is often more attractive), and of course can tell a story. Best-known early example: Maniac Mansion, 1987. Probable first use: Pac-Man, 1979.

29. True 3D.

We used to fake 3D viewpoints a lot, usually because we didn’t have the CPU power to provide the real thing. Doom was a very clever fake. 3D doesn’t always improve gameplay—consider Lemmings versus Lemmings 3D—but its impact on gaming is incalculable. Even mobile phones are starting to get 3D accelerators. Best-known early example: Microsoft Flight Simulator v1.0, 1982. Probable first use in a game: SPASIM, a Star Trek-themed multiplayer mainframe game, 1974. These were possible only because of the extremely limited number of objects in the landscape.

30. Context-sensitive camera.

A natural advancement on the third person perspective, a context-sensitive camera moves intelligently to follow the action. This enables the designer to use a cinematographer’s skills to present the game from the best angle at every moment. Context-sensitive cameras are excellent for adventure and slower-paced action-adventure games. In fast games, however, there’s a risk that sudden camera movements will be disorienting—to control events at speed, you need a predictable viewpoint. Best-known example: ICO, 2001. First use: unknown. Pre-rendered backdrops (as in point-and-click adventures) and player-controlled cameras (as in Gabriel Knight 3) aren’t the same thing.

31. Procedural landscape generation.

This technique enables designers to create large play spaces without having to build them by hand. If it’s done on the fly, they don’t even have to store them, which was important in the early machines. Best-known early example: Seven Cities of Gold, 1984. Probable first use: River Raid, 1982.

32. Interchangeable dialog playback (aka “stitching”).

This is the practice of assembling audio clips together to produce seamless dialog with varying content. We use it to create credible play-by-play in sports games, where the names of different athletes have to be inserted into the commentary. It has done a lot to create a truly television-like experience. Best-known early example: Hardball III, 1992. Probable first use: 3rd Degree for the CD-i player, 1992.

33. Adaptive music.

Everyone recognizes the power of music to create a mood. In videogames, the trick is to change the music in response to game events, and of course the composer can’t know in advance when they might occur. One approach is simply to play a new track on demand, but the transition can be jarring if not done well. Another approach is layering—mixing harmonizing pieces of music together and changing their volumes in response to the needs of the game. Best-known early example: Wing Commander, 1990.

Possible first use: Way Out for the Atari 800, 1982.

34. Bullet time.

Adjustable time has long been standard in flight simulators; it lets you speed up game-world time in order to get through dull periods quickly. Bullet time is a later innovation. It slows time down while still letting you act quickly, so it creates a feeling of super-speed to go with the more common game sensations of super-strength or super-toughness. Best-known early example: Max Payne, 2001. Possible first use: Requiem: Avenging Angel, 1999.

35. Deformable environments.

Here’s a classic game absurdity: a huge explosion destroys a tank, but does nothing to the walls and windows nearby. Deformable environments correct this and let you literally change the world. This feature poses a risk to a game’s level design because you may be able to get into places the designer didn’t expect you to; but it makes the world much more realistic and lets you solve problems in your own way. Possible first use: Magic Carpet, 1994.

36. Clever indicators for unusual attributes.

Health, speed, mana, lives, ammunition, fuel, and so on all use pretty standard screen indicators: power bars, digits, gauges, repeating small images. Many are borrowed from real-world devices. But what about other, less obvious attributes? Over the years we’ve devised a variety of clever ways to display them—too many to list, so I’m lumping them all together. Some personal favorites: the flickering light in Thief: The Dark Project that indicates how “noticeable” your avatar is; the crosshairs that grow farther apart to indicate reduced weapon accuracy while you’re moving in shooter games; blurring the screen and rendering the controls unreliable to convey that the avatar is drunk or drugged.

Genres

We borrowed many videogame genres from other game forms, but a few genres would not have been possible before the invention of the computer, and represent real design innovation.

37. Construction and management simulations.

Both LEGO blocks and business management games predate the computer, but videogames put the two ideas together for the first time. Best-known early example: SimCity, 1989. Probable first use: Utopia for the Mattel Intellivision, 1982.

38. Real-time strategy games.

Turn-based computer war games had their roots in classics like the Avalon Hill board games, and many of them looked like board games too, with square counters representing units on a hexagonal grid. The addition of real time play made strategy gaming far more accessible to the general public, although purists would complain that RTS games replace true strategy with rapid mouse clicking and resource management. Best-known early example: The Ancient Art of War, 1984. Probable first use:

Stonkers for the ZX Spectrum, 1983. A related genre is real-time tactics, games that concentrate on individual battlefields (e.g. the Total War series) and eliminate the resource-manufacturing aspects of RTS games.

39. Fighting games.

Apart from real-world sports and the 1960’s toy Rock ’Em Sock ’Em Robots, I can’t find any examples of fighting games that predated the videogame. Many games include fighting elements, but true fighting games concentrate on mêlée combat without exploration or puzzle-solving. Fighting games have moved so far beyond real-life martial arts (incorporating magic powers, fictitious weapons, and unrealistic physics) that they constitute a major innovation of their own. There are now many sub-genres, but the common element is hand-to-hand fighting without ranged weapons. Possible first use: Heavyweight Champ coin-op, 1976. Best-known early example: Street Fighter, 1987.

40. Rhythm, dance and music games.

Timing challenges are as old as Pong, but games specifically based on rhythm arrived comparatively recently. Games about making music are increasingly popular too. By avoiding mindless repetitive violence, they also attract a larger female audience. Best-known early example: PaRappa the Rapper, 1996. Possible first use: Tempo for Sega 32X, 1995. (Music Construction Set, 1984, doesn’t count as a game.)

41. Artificial pets and people.

People love watching little critters live their lives, especially if you don’t have to feel guilty about letting them die (or if they’re immortal and can’t die at all). Training and nurturing them and buying trinkets for them are all part of the fun. The Sims is the best-selling PC game of all time; Nintendogs is a massive hit on the Nintendo DS. Possible first use: Little Computer People, 1985. Best-known early example: Dogz, 1995.

42. God games.

This genre is a mashup of construction and management simulations, real-time strategy games, and artificial life games, with some extra qualities all its own. In a god game, you assume the role of the god of a group of people, and your job is (mostly) to help them prosper. The key features are indirect control—you can influence your worshippers through your actions, but you cannot give them explicit orders—and divine powers such as changing the landscape or causing natural disasters. God games let us make volcanoes on demand; what more need I say? Probable first use: Populous, 1989. (Some people consider Utopia, 1982, to be a god game, but I class it as a CMS because the player’s powers aren’t truly godly. The claims of the Firaxis PR department notwithstanding, Civilization is not a god game.)

43. Social and dating games (with or without sex).

I can only find one non-computerized dating game, Milton Bradley’s 1965 board game Mystery Date. Computerized dating sims are a major phenomenon in Japan. Many use dialog tree conversation, in which saying the right thing to a prospective partner leads to a closer relationship. Some have complex systems of attributes not unlike those in role-playing games, but the attributes describe a character’s romantic appeal rather than his ability to whack monsters. Possible first use: D??ky?′sei (Classmates), 1992.

44. Interactive movies.

This genre came and went, and good riddance to it. It’s a world-changing design innovation because it proved so clearly to be a creative dead end that everybody knows not to make interactive movies any more—although the term is still used at times to describe the cinematic quality of games in other genres. Interactive movies taught us, by negative example, that gameplay comes first, period. The CD-ROM drive first made them possible, and in their heyday, they sold tons…until the novelty of watching tiny, grainy videos wore off. Best-known early example: The 7th Guest, 1993. Probable first use: Dragon’s Lair coin-op, 1983.

45. “Games for girls” (not women).

The game industry ignored girls entirely for most of its early history. In the mid-1990s there was a short-lived vogue for making games for girls, but it was mostly marketing hype and a lot of girls got ripped off by shoddy products in pink boxes. The idea has since been revived somewhat; witness the Bratz series based on the (in)famous dolls. A degree of controversy surrounds games for girls, as some people are concerned that fulfilling girls’ shopping fantasies is not as socially responsible as fulfilling boys’ violence fantasies. Other games aimed at the girl market are less stereotypical, e.g. the Nancy Drew adventure games. Best-known early example: Barbie Fashion Designer, 1996. Probable first use: Barbie, 1991. (Although Pac-Man and Centipede, both from 1980, were popular with female players, neither was explicitly marketed to girls. Plundered Hearts, 1982, was aimed at adult women.)

Play Styles

Different ways that people play, and how designers facilitate them.

46. Brag boards (aka high score tables).

The earliest arcade games didn’t have them. You could beat your buddy if the game was multiplayer, but only you and he knew it. The brag board, which records your initials along with your score, lets you be king of the hill until someone bests you, an irresistible challenge to competitive players. First use: Asteroids, 1979.

47. Save game.

The subject of religious warfare ever since it was invented, with those who enjoy the challenge of making it through a difficult section with no safety net in one camp, and those who want to stop and start play on their own timetable in the other. For good or ill, depending on your perspective, the ability to save profoundly affects your play style. There are many ways to implement saving, however, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. I include level passwords (for machines with no storage media) and checkpoints in the same category. First use: lost in the mists of time.

48. Modem-to-modem and networked play.

Modem-to-modem games let people play together in pairs. Although an important step forward, their biggest weakness was in the lack of a matchmaking facility—you had to know someone else who owned a modem and a copy of the same game. Then we got networking, and the medium exploded. However, networked play actually existed before personal computers. Best-known early example: RabbitJack’s Casino on the Quantum Link service for Commodore 64 machines, 1986. Probable first use: Maze Wars on networked Imlac minicomputers at MIT, 1974.

49. Multiplayer dungeons.

Combine the fun of exploration in games like Zork with the fun of multiplayer play, and you get the multiplayer dungeon. MUDs are the direct precursors of today’s wildly popular MMORPGs. In South Korea, they’re a national mania. The earliest version was not networked, but played on a timesharing mainframe. First use: MUD, at the University of Essex, 1979.

50. Party games.

We’ve always had multiplayer games, but party games are different—they’re designed to provide entertainment in the context of a real party, a group of people enjoying each other’s company. Instead of immersing players deeply in a fantasy world, party games give them lots of mini-games to play and laugh about. First use:

Mario Party, 1998.

Those are the fifty design innovations that I’ve selected, some that were extremely important, others that will be increasingly so in the future. Opinions will doubtless vary as to their significance, and I may have omitted something that others find essential. I look forward to further discussion!(source:next-gen)